KONDOA IRANGI.

Kondoa rock-art sites

The Kondoa Rock-Art Sites, or Kondoa Irangi Rock Paintings, are a series of ancient paintings on rock shelter walls in central Tanzania. The Kondoa region was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2006 because of its impressive collection of rock art.

These sites were named national monuments in 1937 by the Tanzania Antiquities Department. The paintings are located approximately nine kilometers east of the main highway (T5) from Dodoma to Babati, about 20 kilometers north of Kondoa Irangi town in the Kondoa district of the Dodoma region of Tanzania. The boundaries of the site are marked by concrete posts. The site is a registered national historic site.

The landscape of this area is characterized by large, piled granite boulders that make up the western rim of the Maasai steppe and form rock shelters facing away from prevailing winds. These rock shelters often have flat surfaces due to rifting, and these surfaces are where the paintings are found, protected from weathering.

These paintings are still part of a living tradition of creation and use by both Sandawe in their simbó healing ceremonies and by Maasai people in ritual feasting. The persisting significance and use of the rock shelters and their art suggest that there has been a

cultural continuity between the various ethnic and linguistic groups of people who have resided in the area over time. About 1970, Sandawe men were still making rock paintings. Ten Raa inquired into their reasons for doing so. He classified these reasons as magical (depicting the animal that the painter intended to kill), casual, and sacrificial (on specific clan-spirit hills and

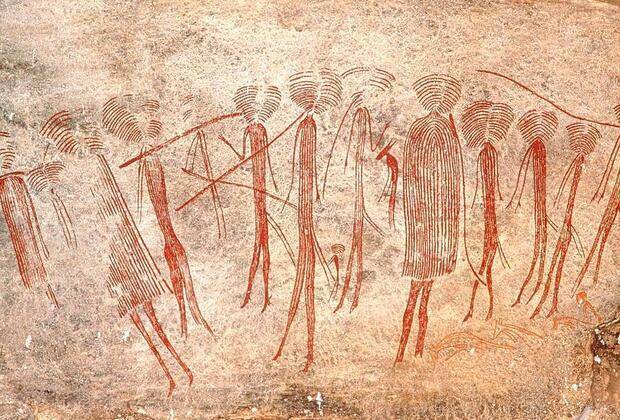

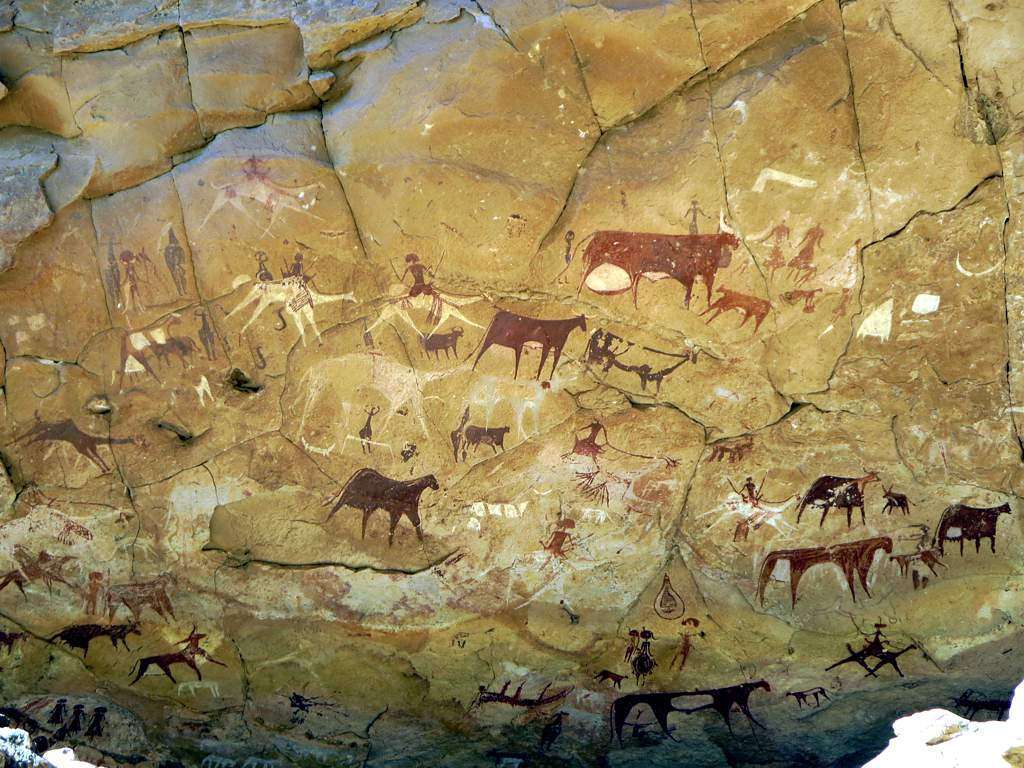

depicting rain-making and healing ceremonies). The paintings depict elongated people, animals, and hunting scenes. Older paintings of the naturalistic tradition are generally red and associated with hunter-gatherers, not only in Kondoa but also throughout the Singida, Mara, Arusha, and Manyara regions of Tanzania. The naturalistic tradition paintings are frequently superimposed by a more recent late white style, often depicting cattle, that has been attributed to Bantu farmers and thought to post-date the Bantu expansion into the area. White and red paintings have been attributed to Cushitic and Nilotic pastoralists. Except for the paintings whose creations were recorded in recent times, there is no direct dating evidence. Bwasiri and Smith point out that the rain-making ceremonies of the Sandawe are of Bantu origin, derived from a long history of cultural contact with Bantu and other peoples, and they suggest caution in using recent ethnographic evidence to interpret the history of the art.

The Kisese II rock shelter, in the Kondoa area, has art of the naturalistic tradition on the walls and evidence of occupation on the floors dated to more than 40,000 years ago. “Africa’s rock art is the common heritage of all Africans, but it is more than that. It is the common heritage of humanity. There are many individual sites within the UNESCO World Heritage boundaries. Estimates for the number of decorated rock shelters in the region range between 150 and 450. The following are some of the most important, notable, or otherwise well-excavated sites:

KISESE II ROCKSHELTER

The Kisese II Rockshelter is part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site located in the Kondoa region of Tanzania. The site contains transitional assemblages from the Middle to Late Stone Age. The rockshelter has preserved diverse paintings, beads, lithics, pottery, and other artifacts. It is studied for its insight into the major social transitions that were taking place during the late Pleistocene and Holocene eras.

The site was also used for the burial of seven Holocene individuals. There are not very many well-dated sites that span this transitionary period, so Kisese II excavations have been very informative.

A significant number of Ostrich bird eggs were used for radiocarbon dating of the site, the oldest of which dates to 46.2–42.7 ka cal BP. The Kisese II Rockshelter began to be excavated by Mary and Louis Leakey in 1935, and Raymond Ins kept expanding the excavation trench in 1956. Inskeep uncovered the large collection of ostrich eggshell (OES) beads that allowed for later radiocarbon dating of the site, in addition to almost 6,000 lithic artifacts in situ. The stratigraphic nature of the depositions was also studied by both Inskeep and the Leakeys in an attempt to date the site.

The lithic artifacts at Kisese II range from flakes to cores, mostly made of local quartz-based stone and mostly made by using the Levallois method or the LSA microlith method. The site supports the idea that some MSA technologies, such as this method of making stone tools, persisted well into the LSA. Tryon et al. proposed that the transitionary period may have been a minimum of five to ten thousand years.

MUNGOMI WA KOLO (Mungomi wa kolo site 1)

Mungomi wa Kolo is the local title for the site known as Kolo 1. The art in this rock shelter is mostly composed of fine-line red ochre drawings depicting various people and animals.

In 1929, T. A. M. Nash published an overview of some red ochre paintings he discovered near Kondoa-Irangi.

Nash recognized the granite shelters to be an ideal place for rock art and consequently scoured the hillside for drawings, proving himself correct after about ten minutes. One of the paintings depicts a human figure holding a stick and an elephant. Nash

commented on the peaceful posture of the human, doubting that the drawing was intended to depict a hunting scene. Other paintings portray giraffes, a possible rhinoceros’ fragment, a humanoid figure composed of concentric circles in the head, and

continuous lines from the top of the head to the rest of the body, and some other figures whose intended depictions were unclear.

Ethics in Archeology

View from the top of the rock art site Due to the spiritual significance that many of these rock shelters hold for the contemporary inhabitants of the area, great care must be taken when excavating these sites. According to UNESCO World Heritage Paper 13, the local agro-pastoral Irangi people still use some of these sites for ritual healing purposes. Some of these ritual practices are said to threaten the integrity of the paintings, such as the practice of throwing melted animal fat.

The Tanzanian government has yet to recognize the local belief systems, so there is friction regarding the management and conservation of the sites. This is not an isolated problem; decolonization of African archaeology as a whole is an ongoing project.

Kondoa Irangi Rock Paintings are thousands of years old, well preserved, and easily accessible; they tell us the story of our ancestors in the heart of Africa. Their perception of the world, their everyday lives, and their beliefs

In the 1950s, Mary Leakey, a British paleoanthropologist, started documenting these rock paintings and reported that these were the second most extensive rock painting sites in Africa, next to Tassili N’Ajjer in Algeria.

This is absolutely one of the most fascinating places we visited in Tanzania. The tradition of rock paintings has survived until very recent times, some of which date back to the 1960s, and today the site is still used by the Irangi.

tribes, the Warangi and Wasi communities, for their rituals. And this is probably one of the most fascinating things about this unique UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Dating is not easy, but the paintings were initially thought to be dated between 1500 and 6000 years ago on average, but recent new technologies have dated them between 19000 and 30000 years ago. And considering that some

of them are very recent; this region contains the history of the population of this area over the past thousands of years in Kondoa Irangi